About

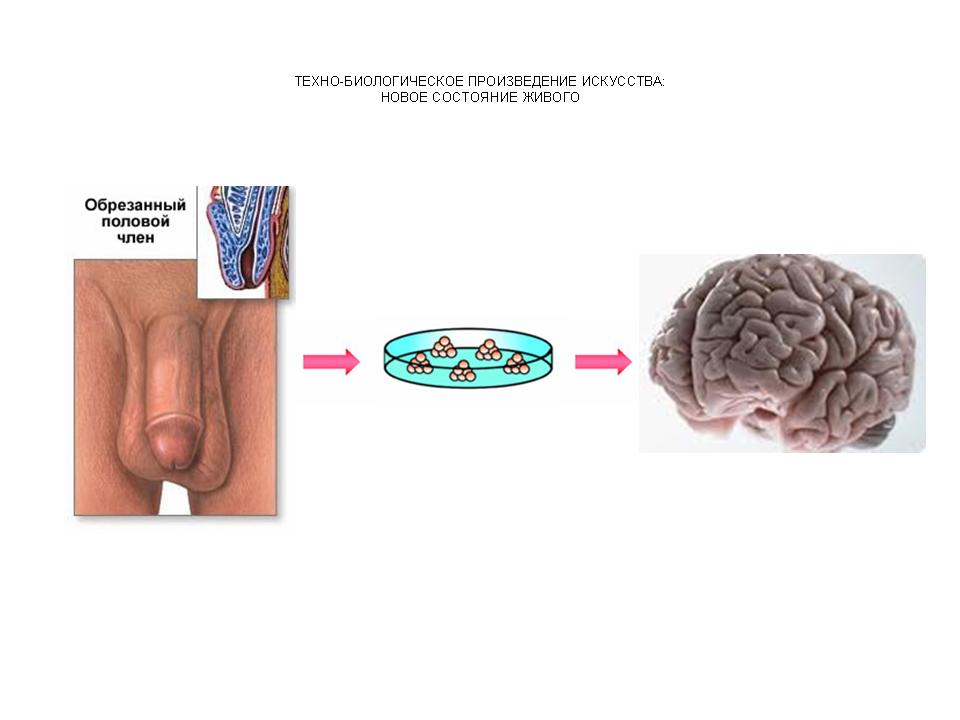

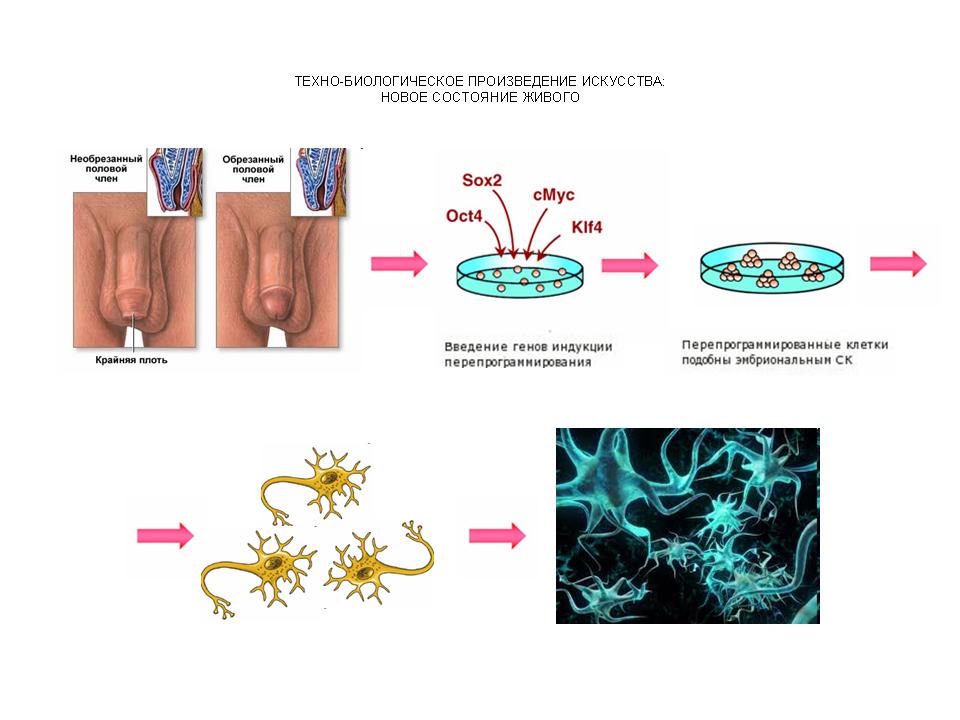

Interested in how art has the potential to problematise the shifting forces that govern and determine life, death and personhood, we developed in potēntia: a speculative techno-scientific experiment with disembodied human material, diagnostic equipment and a stem cell reprogramming technique called iPS. Developed in 2007, iPS takes cells from any part of the body and reverse engineers them into an embryonic stem cell-like state. These cells are then tricked into becoming any other kind of cell-type. At a cellular level, IPS not only appears to make ethical dilemmas associated with embryonic stem cell research redundant, but also makes it possible to define and manipulate smaller and smaller unites of live matter, enabling increasingly subtle distinctions between one kind of life and another.

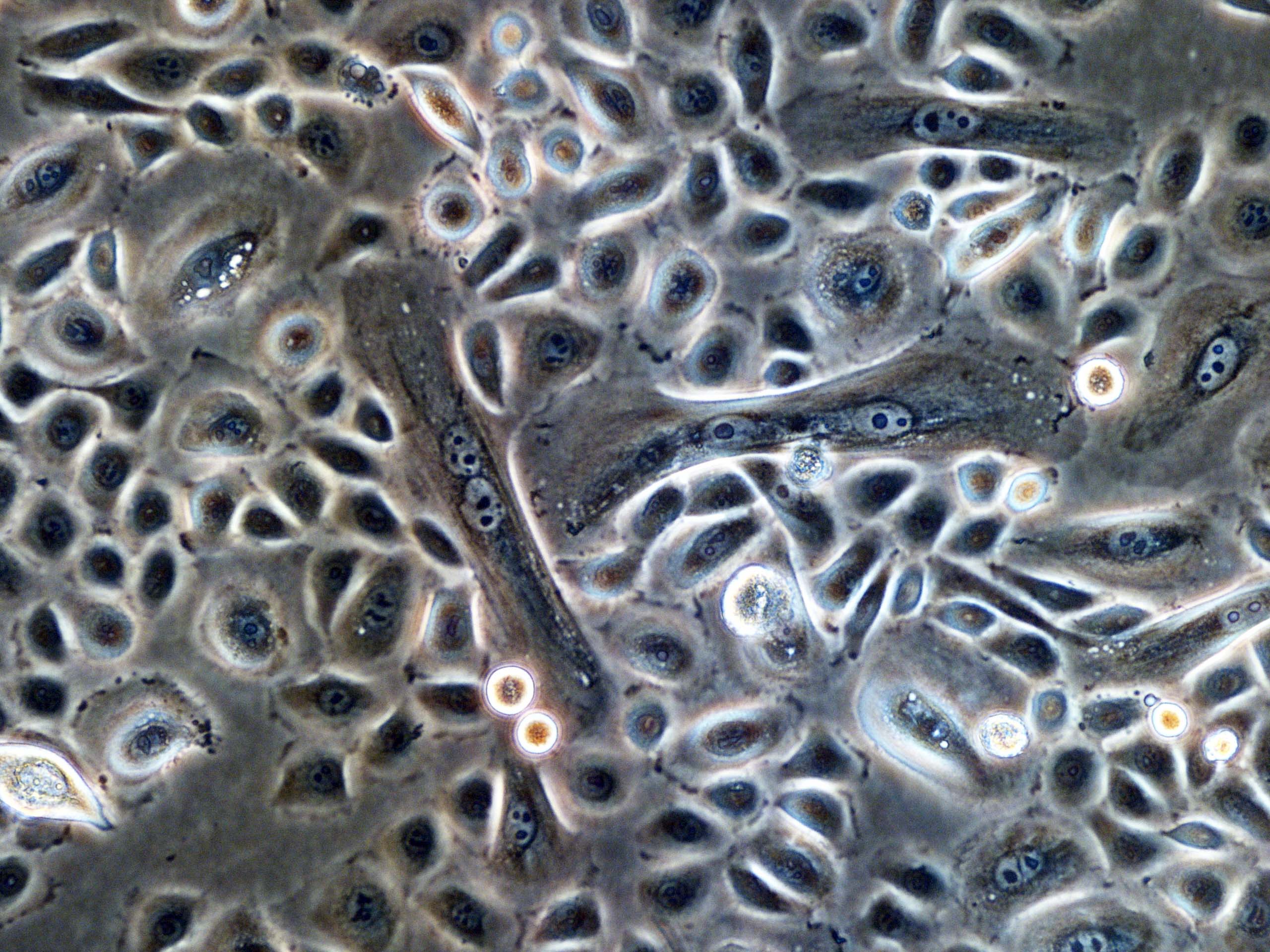

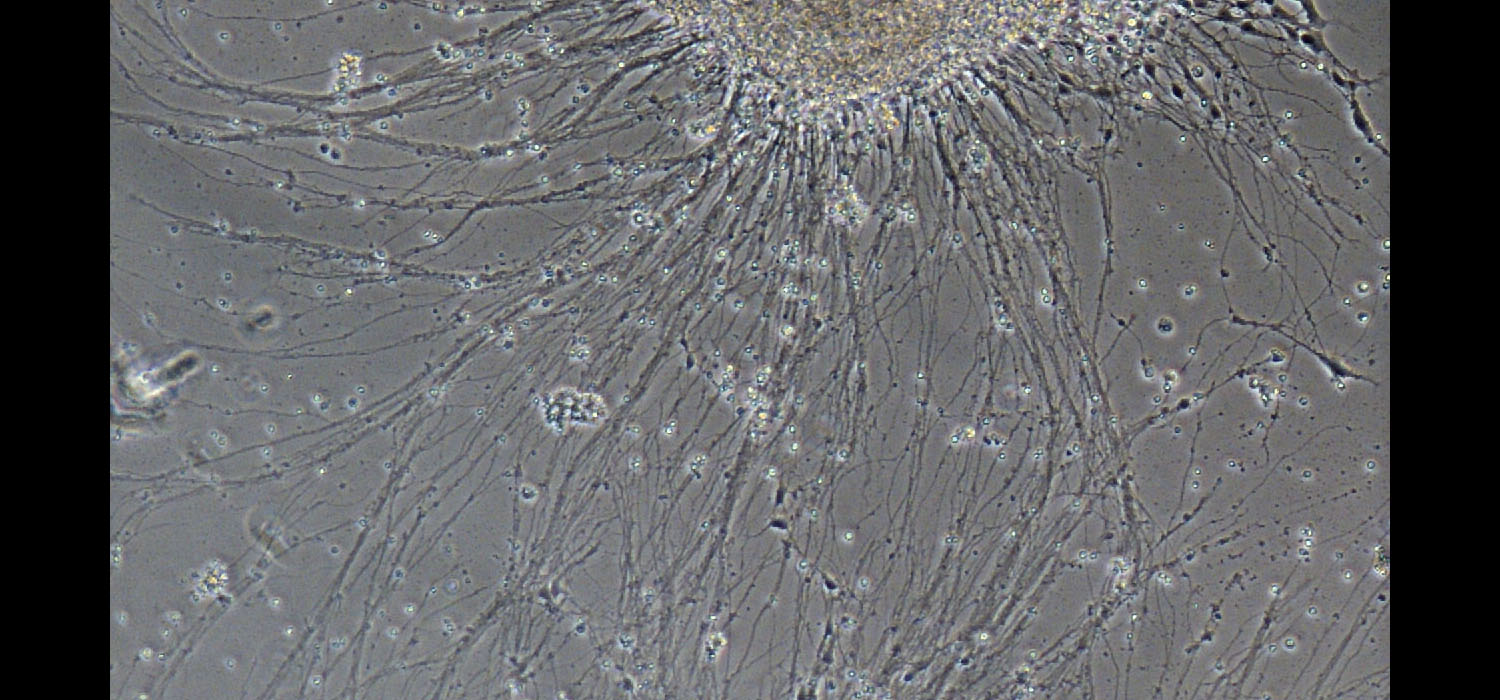

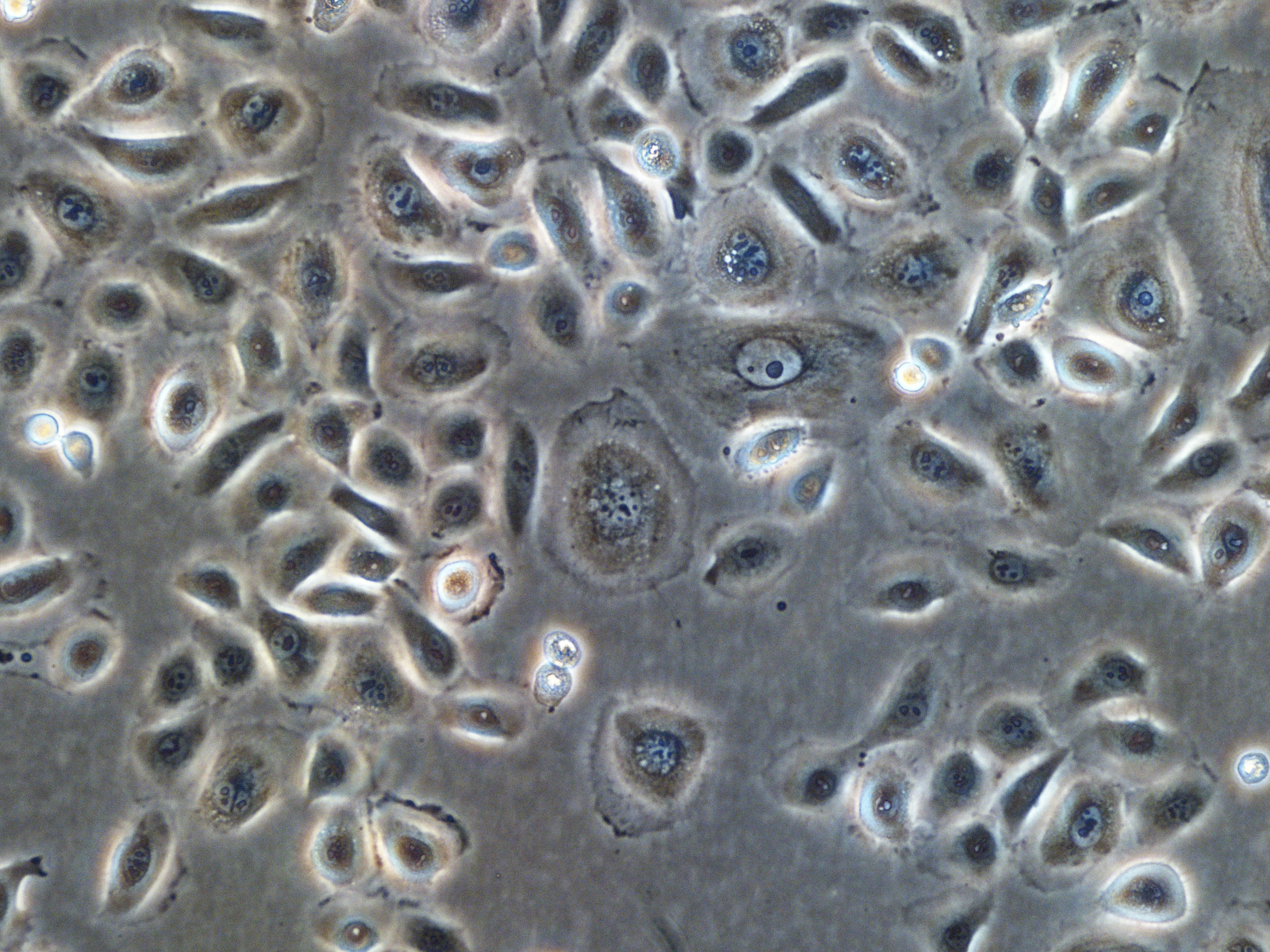

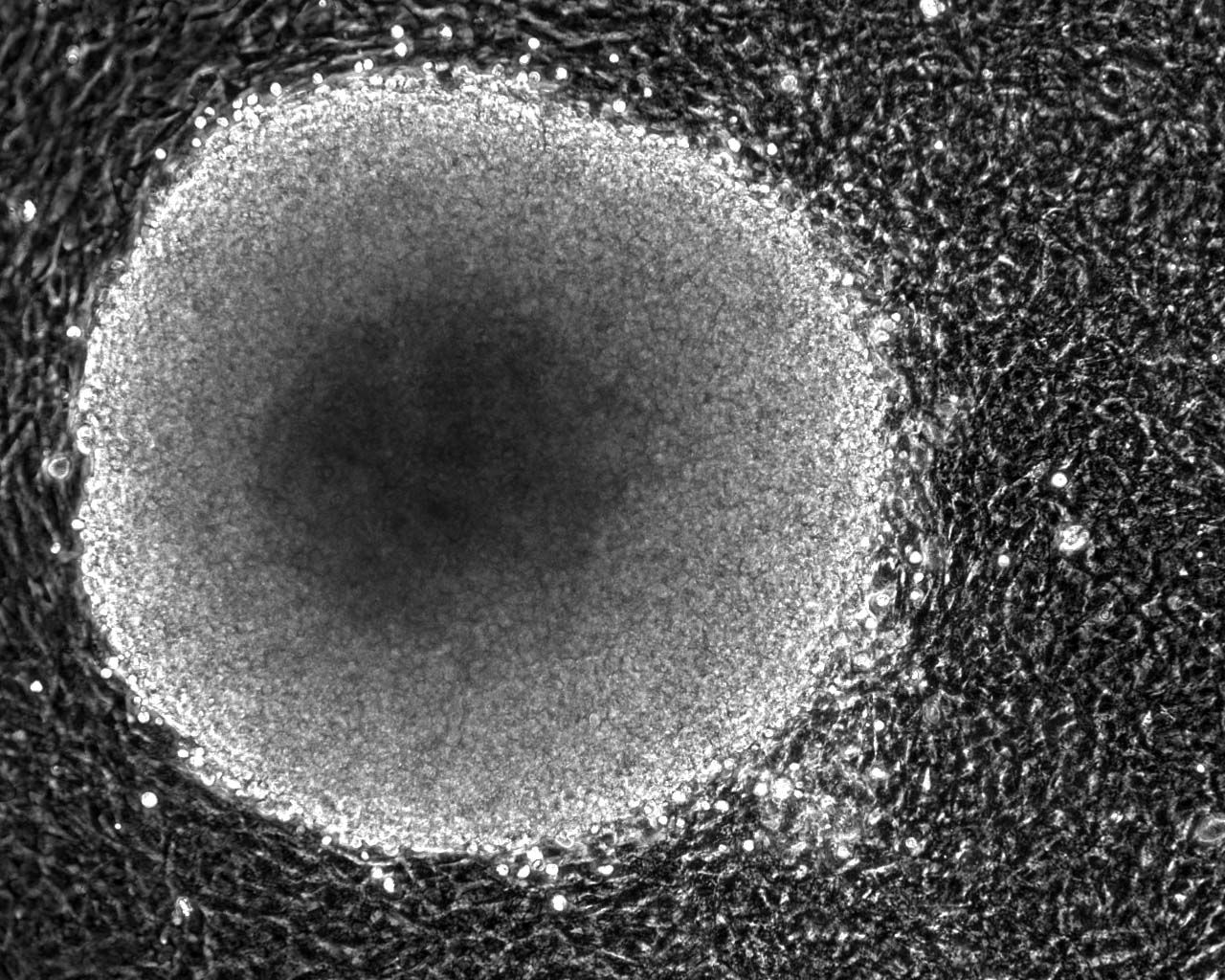

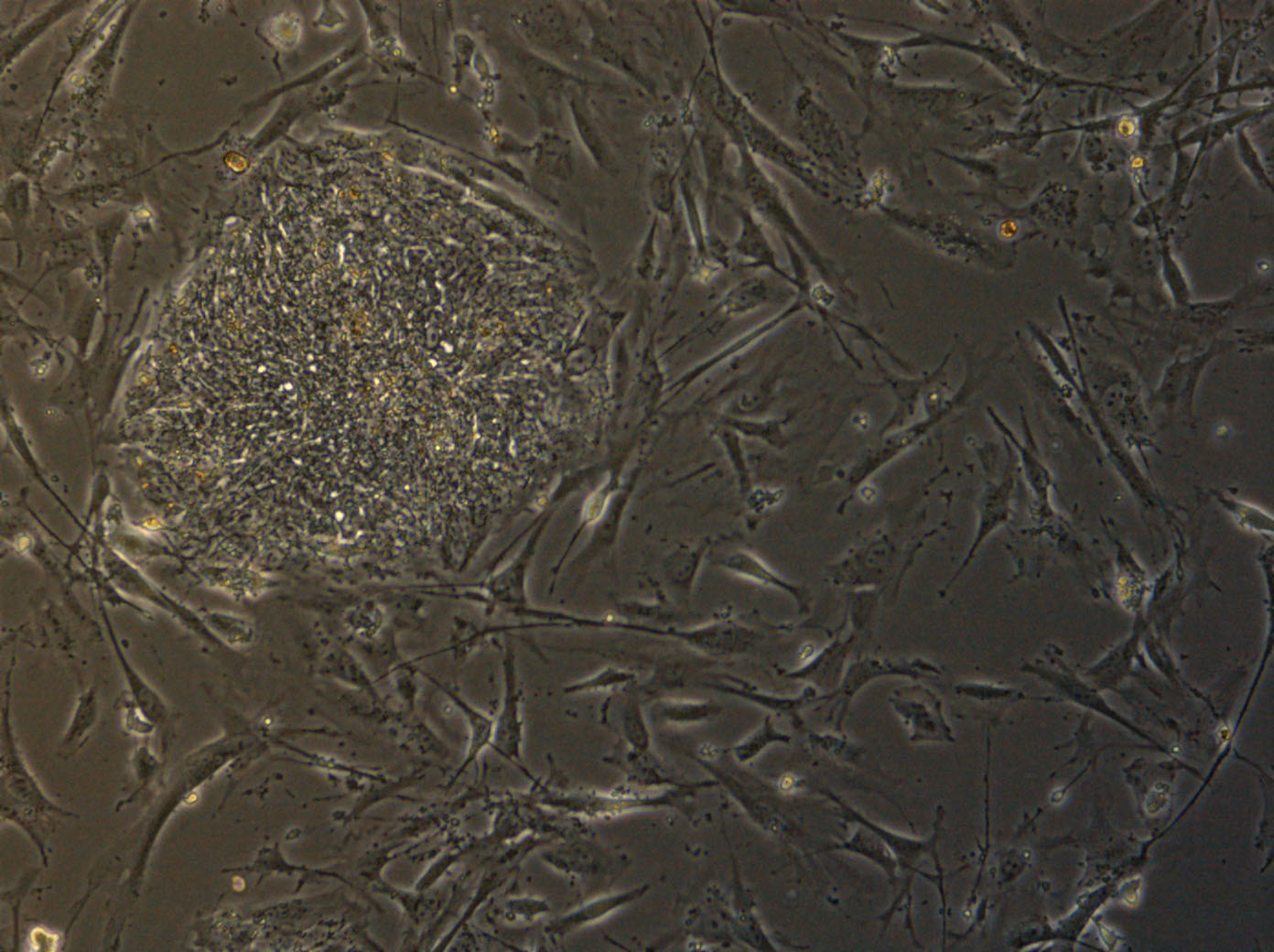

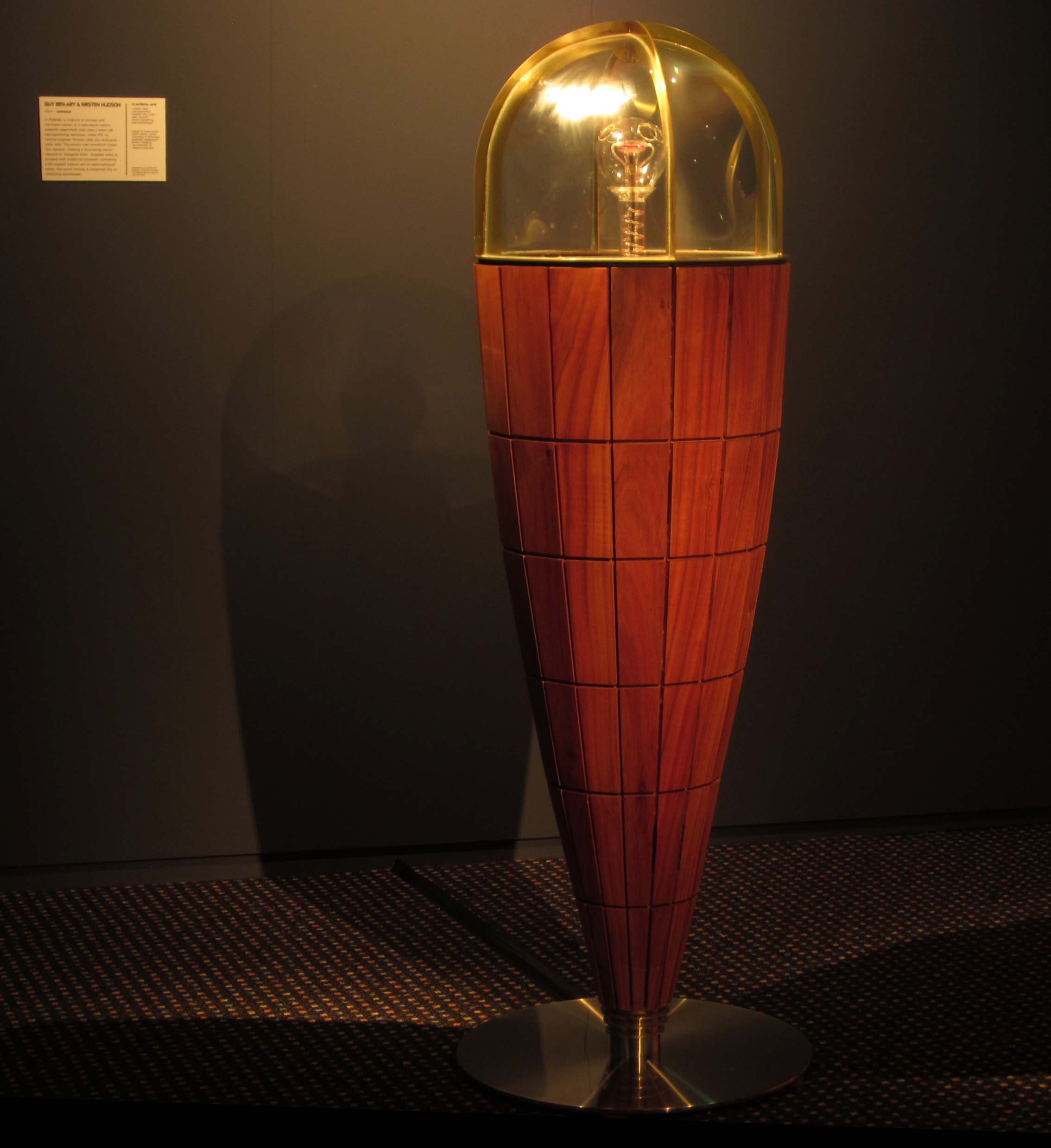

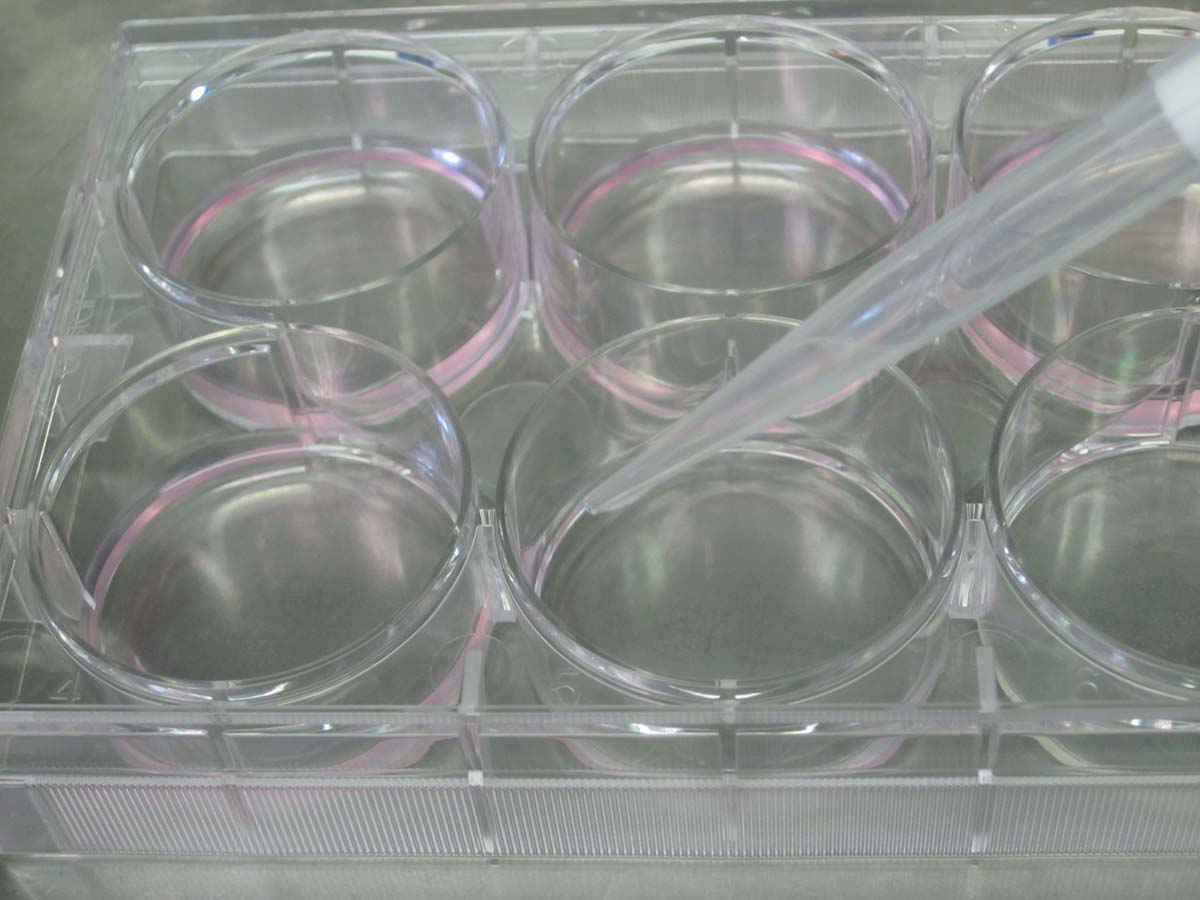

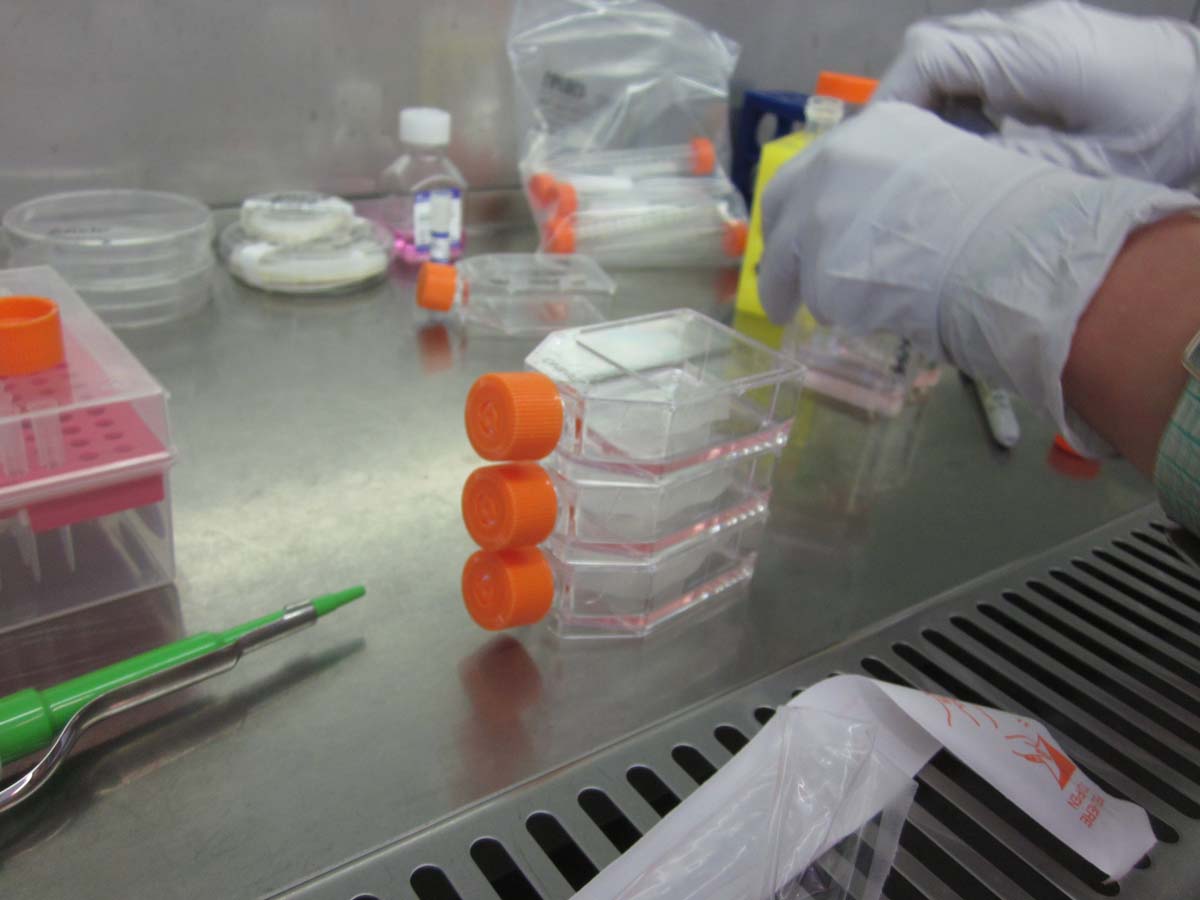

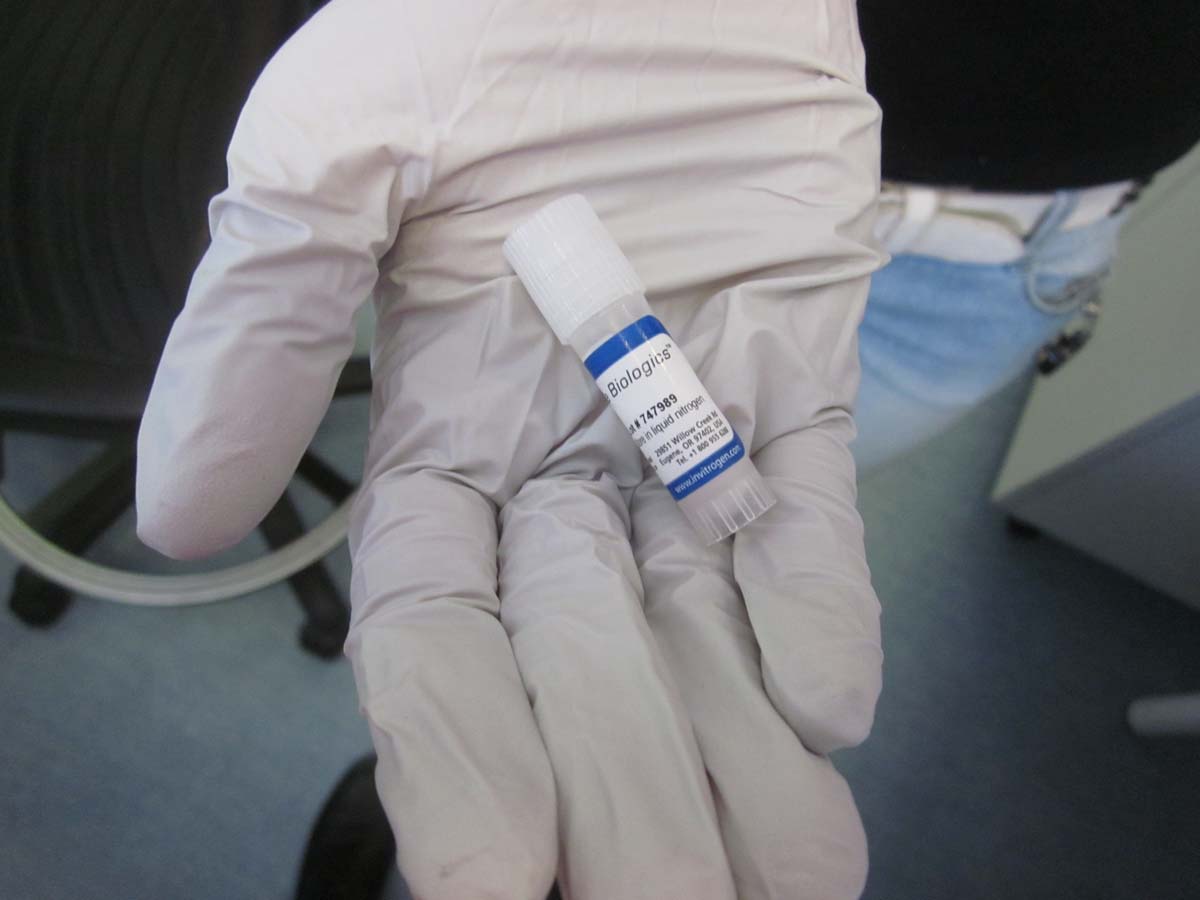

Beginning with human foreskin cells purchased on-line, we use iPS to reprogram foreskin cells into stem cells that we then transform into neurons. What results is a real functioning neural network or biological brain created from foreskin cells. Encased within a purpose-built sculptural incubator containing a DIY bio-reactor and multi-electrode array that converts electrical activity from the neural network into an unsettling sound-scape, our alchemical transformation of foreskin into a brain ironically challenges the modern belief that consciousness is the measure with which life and personhood is judged.

Embodying the unsettling possibilities of the not dead, but not fully alive, our use of iPS questions western culture’s fetishisation of consciousness and shows that rather than being a concrete/discrete category, who or what is called a person is a highly contingent formation that is neither stable nor self-evident. We ask: as it is now possible to bio-engineer a neural network or biological brain, what potential do we now have to bio-engineer conscious, sentient beings and where exactly would these liminal lives fit within our problematic anthropocentric species hierarchy?

Gallery

Conceptual Framework

The politics surrounding assertions and denials of personhood have recieved a great deal of attention in the last two decades as developments in the life sciences and biotechnology have destabilised the genealogical, teleological and evolutionary grand theories through which the category of life has been apprehended. This has meant that rather than being easily comprehensible, stable and obvious, who or what is called a person is now considered to be a highly contingent historical formation; both site and source of ongoing cultural contests and conflicts. Together with discursive power arrangements, scientific practice/s shape understandings of how life, death and personhood are attributed, contested and enacted, such that we are now witnessing growing numbers of liminal lives who hover in an ambiguous zone between life and death. Not dead-but-not-fully-alive, liminal lives are brought into being through the workings of biomedical technique together with legitimating socio-economic and bioethical apparatus’ and sustained by modern medical practices. They are boundary beings whose ontological status is not clear and are subject to continuous transgressions as they exceed and challenge dichotomies: organic –artificial, autonomous –dependent, human –non-human, living –inanimate, coherent –hybrid.

The Approach

By encouraging engagement with, and critical reflection on, a unique cultural moment where we are witnessing the unprecedented evolution of bio-medical modes of liminal lives: transfusion, transplantation, implantation, deep coma, brain death, cryogenic preservation, IVF, etc, we believe that art plays an important role in the public debate on the challenges arising from the existence of liminal forms of life. Redeploying disembodied human parts (foreskin cells) a stem cell reprogramming technique called induced pluri-potent stem cells (iPS) as well as a diagnostic technology called a multi-electrode array to create a functioning neural network or biological “brain”, in potēntia is a liminal boundary creature that ironically challenges the modern western fetishisation of consciousness and personhood, particularly how thinking is the measure with which humans and non-humans are judged. Offering critical analysis of cultural, social and political consequences of techno-scientific achievements, in potēntia transgresses the boundaries between life and death (being and non-being) and in turn forces a remapping of the notions of life, death and personhood, such that we can start to comprehend the limitations of our current understanding of what it means to be “alive” and what it means to be human.

Philosophical Questions

Initially hailed as a technology that would help resolve some of the ethical dilemmas associated with embryonic stem cell, it is now clear that iPS cell technology has transformed the ethical landscape of stem cell research. If iPS cells can be derived from any living cell and have the potential to become any living cell, there are now some fundamental philosophical questions regarding how we determine where life begins and ends, as well as how we evaluate the ontological status of cells. At a cellular level, iPS cell technology now means we have the ability to define and manipulate smaller and smaller unites of live matter, enabling increasingly subtle distinctions between one “life” and another. With such an explosion of “life”, perplexing hiercharies begin to emerge as we start to shift away from old standards for determining life: “Are you breathing?” “Is your heart beating?” “Are your cells still intact and not putrefying?” -in favour of a more demanding standard: “Are you a person?” “Is what makes you “you” still intact?” Previously the domain of philosophers and priests, today it seems as if medical practitioners are predominantly determining our legal humanity based upon ideas of personhood/mind/brain capability and function rather than traditional biological/matter criteria.

It is important to note that the brain only started to take on importance as the organ or region of the body that determines life or death (or personhood) during the 18th century enlightenment. Previously ancient Egyptians and Greeks saw the heart as the primary organ that determined life, while early Christians and Hebrews believed life was indicated by the breath. However, when automated processes (breathing/circulation) were separated from sensation and volition, which was based in the brain, the move towards defining the brain as the pivotal organ of where life resides in the body began. This led to philosophers such as Rene Descarte famously declaring: “Cogito ergo sum” or “I think therefore I am”, which not only became a fundamental phrase in western philosophy but also established the anthropocentric belief that thinking is needed before any living being can go further in life. This distinctly modern philosophical paradigm placed the thinking brain on a pedestal and clearly marked the thinking brain as the primary signifier of individual existence or personhood within modern western culture.

Historical Perspective

By collapsing the socially coded distinctions between mind and matter to create a live, functioning “brain” out of human foreskin cells, in potēntia is an absurd thought experiment that humorously and ironically challenges the modern western perspective established in the 18th century that “man” is his “brain” and when his brain is functioning “he” is here and “alive” and when his brain is malfunctioning, “he” is gone and “dead”. By literally placing a live, male “brain” on a sculptural pedestal that has been informed by the aesthetics of 18th century scientific paraphernalia, in potēntia raises some interesting ethical questions in regards to why we still seem to be ruled by an antiquated and distinctively modern historical form of personhood, and in turn, with in potēntia we ask: what does it really mean to be alive and be human in the 21st century?

Moreover, rather than privileging a vision-generated, vision-centred lens to interpret knowledge, truth, and reality that is usually indicative of the rationalist dream of the 18th century Enlightenment and science in general, with in potēntia, we chose instead to ask our viewers to listen to the “brain” via their aural rather than visual senses. By modifying a Petri dish with a custom built multi-electrode array, we provide evidence of our “brain’s” existence by converting the electrical activity of neural signals or synaptic output into an unsettling sound scape and literally ask our viewers to experience the “brain thinking”. By creating an object that although appears to contain an empty Petri dish (as the cells are unperceivable to the naked eye) but in fact contains a “live” and active neutral network, with in potēntia we ask viewers to question the means with which they judge and determine truth and reality, and in turn what that might mean in terms of how we currently determine life, death and personhood in the 21st century.

Bio Engineering

In potēntia thus makes us wonder: how do we actually determine life, death and personhood in the 21st century? Are the signs we currently use antiquated and discriminatory? Moreover, as it is now possible to bio-engineer a live neural network (or “biological brain”) from any kind of living cell, and if consciousness resides in the brain, what kind of potential could we now have to bio-engineer conscious, sentient beings for utilitarian purposes? Where would these new forms of liminal “conscious” lives fit within an already destructive and violent anthropocentric species hierarchy? What potential does art have to question the institutionalisation of consciousness and how, over the course of modernity, modern western culture’s fetishisation of consciousness has developed historically distinctive forms of incorporation, power, and normativity? And finally, what exactly would the future look like with other similarly manufactured “brains” or “dickheads” living all around us? Would we even notice?

Collaborators

Dr Kirsten Hudson is a practicing artist, writer and academic based in Western Australia, where she is employed as a lecturer in the Schools of Design and Art and Media Culture and Creative Arts at Curtin University. Her research focuses on the philosophies and histories of the body, informed by gender studies, queer theory and French post-structuralism. Thisinforms an art practice that critically resists and subverts normalising representations, constructions and perceptions of subjectivity, sociality and embodiment.

Her current research projects visually and textually explore: 1. the ethical and aesthetic consequences of stem cell technologies on understandings of life, death and personhood; 2, the potential of the art object to articulate ideas, feelings and experiences of melancholy, nostalgia, memory and mourning in a way that actively challenges the limits and understandings of loss and desireis a practicing artist, writer and academic based in Western Australia, where she is employed as a lecturer in the Schools of Design and Art and Media Culture and Creative Arts at Curtin University. Her research focuses on the philosophies and histories of the body, informed by gender studies, queer theory and French post-structuralism. Thisinforms an art practice that critically resists and subverts normalising representations, constructions and perceptions of subjectivity, sociality and embodiment. Her current research projects visually and textually explore: 1. the ethical and aesthetic consequences of stem cell technologies on understandings of life, death and personhood; 2, the potential of the art object to articulate ideas, feelings and experiences of melancholy, nostalgia, memory and mourning in a way that actively challenges the limits and understandings of loss and desire

Mark Lawson is a lecturer and course coordinator in the School of Design and Art at Curtin University Western Australia. His study area is 3D Design Product Furniture and Jewellery design. His research work is developing and applying digital information in direct driving of manufacture items. Instigating changing technologies as creative tools that go beyond economics and predetermined outcomes.

Mark Lawson has a Hons degree in three dimensional design and master’s degree in industrial design from University of Central England Birmingham UK. He practiced design in the disciplines of furniture design and interior fit out contracts in the UK and Australia for 20 years prior to entering design education. Undergraduate and post graduate education in 3D Design provides the creative questioning and opportunity to test and refine values and directions in design practice.

Associate Professor. Stuart Hodgetts (SH) is currently Director of the Spinal Cord Repair Laboratory in the School of Anatomy, Physiology & Human Biology, at the University of Western Australia (UWA). He has extensive knowledge and expertise in cell based transplantation therapies and has been devoted to this research since 1998. Previously, SH has worked at the University of Essex, UK where he obtained his Ph.D. did his first postdoctoral appointment, before working overseas at the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation, USA.

SH returned to Australia and joined UWA in 1998, conducting research in cell-based transplantation for neuromuscular diseases such as muscular dystrophy, and since 2004 in the repair of spinal cord following injury using stem cells. He is developing technologies for the use of Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) for use in spinal cord injury, and is also using this in a number of art/science collaborations. In particular as part of a collaboration with Guy Ben Ary (also at UWA).

Since 2005, SH has been involved in the generation of nearly $3 million in research funds and has published in many highly ranked peer reviewed journals. As a member of Academic staff he teaches undergraduates and postgraduates (currently supervision of 5 PhD students). SH is an active member of committees at the School and Faculty levels and is also Chair of the Animal Users Group at UWA. In addition, he has had a long standing relationship with Symbiotica (ANHB, UWA), involving collaboration with many artists and residents. A long standing advocate of this cross-disciplinary research, he is currently Symbiotica’s Scientific Consultant and Adviser. Over the years SH has been an invited speaker for his Science/Art work at; ANZCAART, The Body, Art and Bioethics Conference, The 6th European Meeting of the Society for Literature, Science & the Arts, and has conducted a Tissue Engineering workshop in the UK as well as exhibited works in collaboration with Symbiotica at ISEA. SH has also recently been involved in funding successes together with Guy Ben-Ary and Ionat Zurr from Symbiotica.